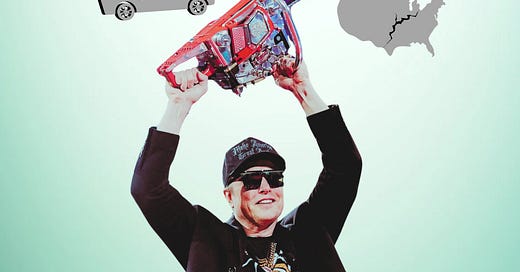

You buy it, you break it

Understanding Elon Musk's MO. Plus, the Pope on taxpaying, and “doomscrolling methadone”

In 2023, Twitter was a vibrant social media platform. That October, Elon Musk bought it — then broke it.

As one commentator put it, “Twitter, which is no longer called Twitter, is a sad shell of its former self…”

Lest we think this was an anomaly in an otherwise productive career, consider this: was it actually the strategy? And was the next thing Musk set out to purchase and then break… the U.S. government?

While campaigning for Donald Trump last November, Elon Musk claimed that he had paid more than $10 billion in taxes, making him the ”largest individual taxpayer in history.”

“You’re welcome,” he said, smiling broadly in response to scattered applause. He explained later, “I was happy to pay the taxes, I don’t mind, you know.”

Still, he was disappointed when the IRS did not send him a “little plastic gold trophy or something like that or a cookie or something but I didn't get anything.”

President Donald Trump corrected that injustice: When he entered the White House, he handed Musk the keys to the entire federal government.

And to think… Musk would have settled for a cookie!

Much has been written about Musk and his unofficial Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) operating well outside of established law and processes in their efforts to intervene in the functioning of the federal government.

I don’t want to rehash that here. I want to focus on why Musk would be handed this much power in the first place.

Though he appears to be exiting his role at DOGE, the impact of Musk’s indiscriminate cuts, math errors, and false claims about “taxpayer savings,” will likely be felt for years. How did we get here?

We can state the obvious: it’s unlikely Musk would have been given this power if not for his money.

On one hand, his enormous success as an innovative entrepreneur is heralded as evidence of his superior intellect and problem-solving capacity. If it were true that those skills could be seamlessly applied to improving “government efficiency” (which there is no evidence of), then that would not be wholly problematic. But it’s never just been about that.

Musk’s elevation to “co-president” seems to have been based, at least in part, on his position as a mega-taxpayer as well as a mega-donor to Trump’s and his chosen candidates’ campaigns. Put simply, he bought his position of influence.

This should concern Americans who believe we live in a constitutional democracy, in which everyone is entitled to equal political rights regardless of how much money we wield. One person, one vote, as the saying goes.

And yet this has always been an aspiration more than a description of reality.

Money has always distorted our democracy. And in an era of rising economic inequality, close observers of our system have routinely warned that this would translate into rising political inequality. A system where people can vote not only at the ballot box, but with their dollars as well.

The most obvious culprit is the deregulation of our campaign finance laws, which has allowed a tidal wave of money to flood our elections, and threaten to drown out the voices and votes of ordinary Americans. Musk’s recent promise to “put $100 million into groups controlled by the Trump political operation” — at a moment when his role at DOGE was drawing negative attention for his “boss” — represents an especially public and transactional version of the money-for-access trade countless large donors make.

Less discussed is how taxpaying fits into this picture. Tax scholars identify two visions for how taxpaying relates to citizenship:

fiscal citizenship: the idea that no matter how small one’s tax payments may be, we are all doing our part to pay for the society we are building together. This idea is inclusive and equalizing. It has also, for the most part, been aspirational.

taxpayer citizenship: the idea that those who pay taxes (or pay the most in taxes) have earned more rights and privileges than those who do not (or pay less). This idea is exclusionary and creates a clear hierarchy between citizens based on how much they supposedly contribute to the national kitty. It has been invoked throughout American history to justify elite claims to political power, or conversely, to deny rights to those who are deemed “non-payers.”

Think of organized groups of white “taxpayers” angrily resisting the desegregation of “their” public schools throughout the middle of the twentieth century. Or more recently, Tea Party activists identifying as “we the taxpayers,” and decrying the use of “their” tax dollars to pay for government services for an imaged group of “takers.”

In 2012, Mitt Romney (the GOP’s presidential nominee) embraced this Tea Party talking point, and lamented that 47 percent of Americans “pay no income tax” and are “dependent upon government.” (This, despite the fact that the income tax is only one of many taxes Americans pay.) His Republican colleague, former Rep. Michele Bachmann, went further, explicitly connecting payment of the income tax to political rights by asking, “If 45% of Americans pay no federal income taxes, should they be allowed to vote?”

It is impossible to know what Elon Musk was thinking when he mentioned his status as the “largest individual taxpayer in history.” He was, at least in part, defending himself against reports that he paid relatively little in taxes, like many of his billionaire peers. But it is hard not to also hear it as a flex, a claim to have bought something with his historic tax payment.

What he bought was access and power without accountability. Including the power to defund and defang the IRS itself; to make it nearly impossible for the IRS to collect the unpaid taxes owed by billionaires like him; and to mine private taxpayer data for unknown uses (and also some known ones).

As we reflect on the first 100 days of the Trump administration, many worry that the president’s economic destruction is intentional, enabling Trump to seize more power, and allowing billionaires like Musk to amass even more property and wealth on the cheap. The logic of such theories is akin to: “you break it, you buy it.“

But these arguments are missing a key upstream process. They could only break it because they already believed they had bought it. This administration only had the power to so quickly sow chaos because both the government and the global economy have gradually been taken over by an elite class of billionaires, like Musk. Having allied itself with this new “broligarchy,” the Trump administration has been able to steamroll many of the democratic institutions that would typically check its power.

When we keep this longer accumulation of elite power in mind, the logic flips from “you break it, you buy it” to the inverse: You buy it, then you break it. To your will. To serve your needs. Despite the fallout for everyone else.

One Thing™️ of the week

We can’t all do everything — but we can do one thing each week

One of the big takeaways from my new documentary podcast, When the Wolves Came, is that those who wish to preserve our constitutional democracy need to create as big and diverse a tent as possible. It’s an all-hands-on-deck moment.

But big tents are hard because they require working with people we don’t agree with on everything. The key is finding issues we can work on together.

According to an analysis by All Rise News of data from the 5 Calls civic engagement app, campaigns that currently mobilize the most people (including in red states!) are focused on defending the basic building blocks of democracy — like the need for checks and balances and due process.

My takeaway: Start conversations with others by focusing on the basics — democracy’s common ground. These are things that large majorities of Americans across the political spectrum support.

What I’m consuming

Here are the smart people I’m reading/watching/listening to

The Tax Justice Network reflects on Pope Francis’s views on taxes “as our social superpower”:

In his words: “The tax pact is the heart of the social pact. Taxes are also a form of sharing wealth, so that it becomes common goods, public goods: schools, health, rights, care, science, culture, heritage. Of course, taxes must be fair, equitable, set according to each person’s ability to pay… The tax system and administration must be efficient and not corrupt. But taxes should not be regarded as usurpation. They are a high form of sharing goods; they are the heart of the social compact.”

And at The Conversation, communications and media studies professor Adam G. Klein recounts Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s 2022 advice to US conservatives:

The Western media, he declared at a May 2022 special meeting of the Conservative Political Action Committee in Budapest, are “the root of the problem.” The key to conservatives reclaiming power in the United States? “Have your own media.”

Looks like the Trump administration has taken this advice to heart.

Latest News

If you’re not sick of me yet, a round up of more words from yours truly

I was thrilled to talk to (who knows a thing or two about podcasts, evangelicals, and extremism) about my new documentary podcast, When the Wolves Came: Evangelicals Against Extremism. Check it out at Straight White American Jesus.

Something Light

A little palette cleanser before you go

Icon Jill Lepore discusses how she turned to books during Trump’s first 100 days as a kind of “doomscrolling methadone.”

Pro tip: Listen to the audio version of the article, which is read by Lepore (and not behind a paywall).

If you’ve enjoyed this post… please subscribe to Democracy is Hard and share it with someone who may also enjoy it.